Lane Rebels Biographies

One of Weld’s first converts to abolition was William T. Allan. Born in 1810, Allan was the son of a prosperous Tennessee slaveholder. When his father Rev. Dr. John Allan was called in 1823 to be the Pastor for First Presbyterian Church in Huntsville, Alabama the family relocated there. William’s father was opposed to slavery but felt that Colonization was the best route to emancipation. In 1832 Dr. Allan was visited by Theodore Weld, who influenced William Allan and his brother James to enroll in the Lane Seminary.

When he arrived at the Seminary in 1833, Allen was the first of Weld’s fellow students to become an abolitionist. Together they shared information with the rest of the student body regarding the evils of slavery. This led to the formation of the debate regarding abolition versus colonization, which took place in February 1834. As one of seventeen debate speakers, William Allan presented his powerful first-hand accounts of the atrocities of slavery. At the conclusion of the eighteenth evening of the debate, those in attendance voted that abolition and immediate emancipation was the right course of action to end slavery. Soon after, the students created an anti-slavery society with Allan as its president.

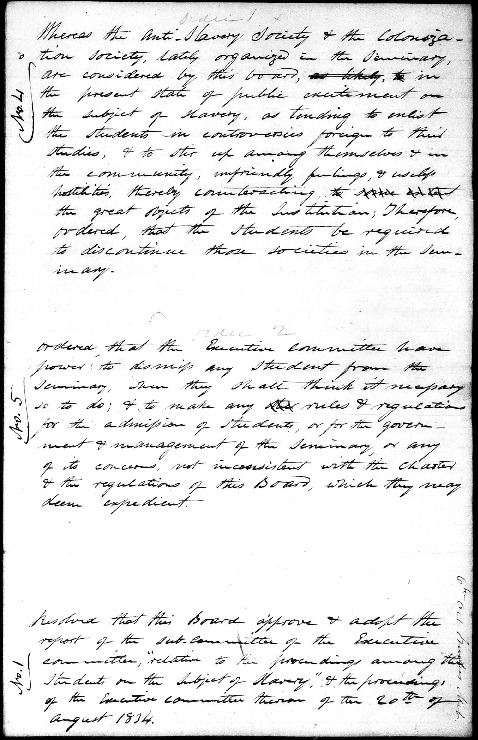

During the summer break of 1834, while the Professors and President Beecher were away, Lane Seminary Trustees appointed a committee to silence the students’ talk of abolition and put an end to all societies on campus. On October 6, the Trustees recommended orders were ratified by the board and William Allan was threatened with expulsion. He and the entire inaugural class of forty students left the seminary. Allan completed his education at the Oberlin Collegiate Institute in 1836 and began work as a lecturer for the American Anti-slavery society for several years. This was courageous and grueling work. Later, his career as a minister took him to the Presbyterian Church in Chatham, Illinois. He died there in 1882, forever known as a Lane rebel.

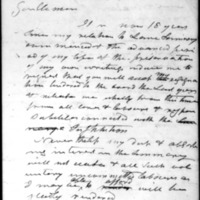

Someone also forever memorialized as a Lane rebel, James Bradley was born in Africa but stolen from there when he was about three years old. After arriving in Charleston, South Carolina he was sold to a slaveholder in Pendleton County, Kentucky named Mr. Bradley. When James Bradley was a teenager his master died, and he was hired out to work off of the plantation. This only lasted until his mistress sent for him, as she could not run the plantation without him. During this time, we don’t know how Bradley learned to read, but he did recount persuading one of his young masters to teach him to write. Bradley had only one lesson. In order to buy his freedom, he planted corn and tobacco on government land and also purchased hogs to sell. After years of toiling almost day and night, in 1833, Bradley had earned approximately seven hundred dollars to buy his freedom and headed for the free state of Ohio.

In Cincinnati, Bradley learned about the Lane Seminary and asked for admission. He became the first black man to study there. In 1834, he was one of the speakers in the Lane debates. It was reported by fellow student James A. Thome, that drawing on his experiences as a slave, James Bradley presented some of the most dramatic testimony during these nightly debates. Bradley then argued that freed African Americans were capable of becoming productive citizens. Bradley reasoned that because slaves were used to taking care of their masters they would take care of themselves better “when disencumbered from this load.” He also presented the idea that slaves wanted “liberty and education,” not expatriation. Following the debates, Bradley left for the Oberlin Collegiate Institute and became that school’s first African American student. A first-hand account of the debates was written by participant, James A. Thome in his speech given at the 1834 annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

One of the most prominent speakers during the 1834 Lane Debate was student James A. Thome. He was born in Augusta, Kentucky to a slaveholding family in 1813. When he entered the Lane Seminary he considered himself a Colonizationist but after only a few months there, was influenced through experience and discussions, to denounce slavery and plead for immediate emancipation. During the debate, Thome professed as a “living witness” to the harsh realities of slavery. His ability to provide a first-hand account of slavery had a vital impact on the debate’s outcome.

Thome was one of the Lane rebels who left and enrolled at the newly formed Oberlin Collegiate Institute. After his graduation, he became a traveling lecturer for the antislavery society. It was dangerous work as he and others were constantly greeted by angry mobs with rotten eggs and bats. This was followed by a commission from the American Anti-Slavery Society to visit the West Indies and report on the results of emancipation there. Along with J. Horace Kimball, they published their findings in 1838 as Emancipation in the West Indies. Thome reported the success of immediate emancipation where the freed people experienced civil and political rights, which included education and suffrage. This report convinced the American Anti-Slavery Society to forge ahead with a demand for immediate emancipation.

Thome returned to Oberlin in 1838 and held a professorship of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres until 1848. From that time, he served as both an Oberlin department chair and the Pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, Ohio. In 1871, he and his family moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee where he was a local church Pastor until his death suffering from pneumonia, in 1873.

The most thorough account of the Lane Theological Seminary debates was written by Henry B. Stanton. His account titled “Great Debate at Lane Seminary” was published by Garrison & Knapp along with a speech by fellow student James A. Thome given at the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society on May 6, 1834.

Stanton was born June 27, 1805 in New London, Connecticut and grew up in a loving, educated family. In his biography, Random Recollections, he recalled the family slave, who had a lasting impact on his life and created his sympathetic outlook for the enslaved. In 1830, he met and was greatly influenced by Charles Grandison Finney who was serving as a visiting pastor for the Third Presbyterian church of Rochester, New York. Then in the spring of 1832, Stanton travelled west to enroll in the Lane Theological Seminary. That summer he participated in a school debate regarding the question; “If the slaves of the south were to rise in insurrection, would it be the duty of the North to aid in putting it down?” (Stanton, 46). During that evening’s debate, he spoke as the only participant who believed that the North should not interfere with slave uprisings. Through his arguments, Stanton then discovered “…it afterwards came to pass that this was the beginning of my life-work…” (Stanton, 47). Stanton proved to himself that he was a passionate abolitionist.

In 1834 while at Lane Seminary, Stanton participated in the eighteen-night debate concerning colonization versus abolition. Immediately following this event he and several other students founded a seminary Anti-Slavery Society. Describing these events, Stanton wrote, “We had a great Anti-slavery debate at Lane Seminary, and formed a society during that fall. Pro-slavery trustees required that we should dissolve it. We refused to do so. They then passed arbitrary rules in respect to discussion, and even conversation, on the subject of slavery at the seminary. A goodly portion of us, who were not to be thus throttled, left. I was on the committee that issued an address in vindication of our course. It produced a deep impression” (Stanton, 48). For the next several years, Stanton was a general agent and Secretary for the American Anti-Slavery Society, travelling and speaking in favor of immediate abolition. He felt that the end to slavery would ultimately come through political means by way of Constitutional amendments. During this time, he was a strong supporter of John Quincy Adams and his fight to end slavery.

On May 1, 1840 Stanton married Elizabeth Cady, one of America’s most outspoken women’s voting rights activists. Together they journeyed to England and attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where Stanton served as a delegate. After spending a year there, they returned to New York where he completed his studies to become a lawyer. Then in 1842 the Stantons moved to Boston for his law practice. Following their move to Seneca Falls, New York in 1847, Stanton entered politics with his election to the state legislature in 1850. During this time, the Stanton’s family grew to include seven children. Throughout his long life, Stanton was regarded as an eloquent speaker and writer who had a great passion for the rights of people of all races and women. He died in 1887 having witnessed the passage of the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments and the end of slavery. Stanton and his fellow debate participants demonstrated the passion they felt for the cause of antislavery.

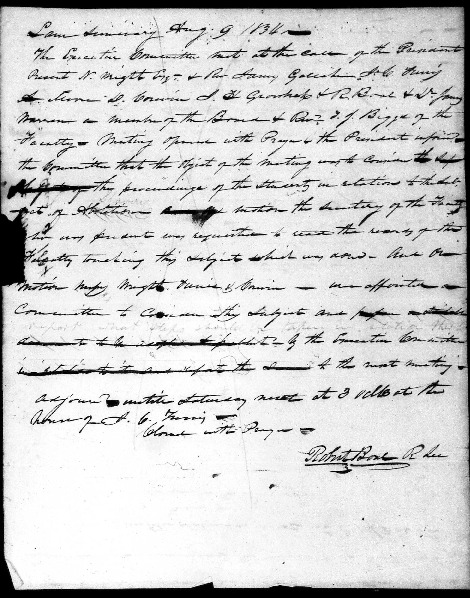

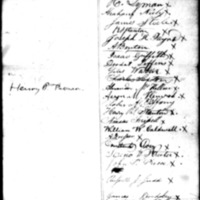

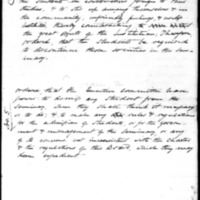

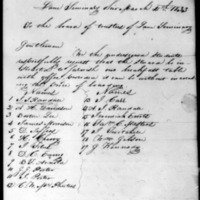

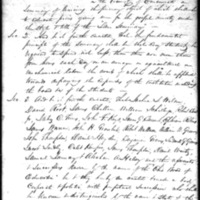

Several primary documents featured on this exhibit on my website, are meeting minutes from a committee that was created to discuss what to do about the radical abolitionist students on campus. After several meetings over the course of a few months, the committee decided, along with the board of trustees, that all societies should be eliminated on campus, except for the societies that deal with the course of studies.